Filmmaker Spotlight: Jon Matthews

Lessons Learned As A First-Time Filmmaker

Published: May 4, 2017

Jon Matthews learned last week that his 2017 documentary OPIOID, INC got accepted by West Virginia Public Broadcasting for broadcast.

It's been an unconventional journey for Matthews getting to this point.

Starting his career as a Civil Rights lawyer, he decided to make a drastic change in his career and enrolled at NYU Film School in 2009 at the age of 31.

OPIOID INC is his second documentary after SURVIVING CLIFFSIDE, a feature-length documentary that premiered at the 2014 SXSW Film Festival and aired on the Sundance Channel. He is co-producer on the upcoming documentary HILLBILLY (Co-Directed by Ashley York and Sally Rubin).

Jon not only makes documentaries, but also produces commercial film work and narrative feature films.

He co-directed the narrative feature film BLACK DOG, RED DOG with James Franco and several other classmates at NYU's graduate film program. And he wrote & directed KHALI THE KILLER, a crime drama produced by Nu Image/Millennium.

We first met Jon back in 2012 fresh out of film school. We decided to check in with him to see how things are going with this crazy journey called filmmaking and any lessons he's learned coming into the film industry as a complete beginner and outsider.

Interview with Jon Matthews

As a relative newcomer to documentaries, what do feel is the toughest part of the process?

The toughest part for me is keeping my mouth shut. I think I get some really great moments when I let the subjects talk. When they get emotional, sometimes I get uncomfortable and I feel the need to say something to break the silence. But, if I can hang in there and keep my mouth shut, I often end up getting some really powerful stuff.

Where/how did you initially get the idea for the Opioid Inc documentary?

I made a documentary, called Surviving Cliffside, that featured a family whose father was addicted to opioids. He lived in a West Virginia trailer park that was a hotbed for drugs. Since 2014, when I completed the film, three of the cast members have died from drug overdose. One of my six-year-old cast members, Brooklyn, found her mother, Cierra, dead on the bathroom floor with a needle stuck in her arm. So, it really all started with that documentary.

Then, last year, I was commissioned to do a film for a group of lawyers who were suing the prescription drug distributors who fueled the pill mills in West Virginia. Being a doc film maker and a former trial lawyer myself, I was in a unique position to understand the legal issues and tell the story in an evocative way. A lot of the footage in Opioid Inc. came from interviews I did for the case against the drug distributors.

Do you find any similarities/overlap with being a lawyer and a filmmaker (or are they two different worlds)?

Well, if I would have been an entertainment lawyer, I would have been set. But I was a civil rights lawyer. So, I don't really know much about intellectual property or contracts or really anything that would help me now. But being a litigator did help in one very important area. And that's knowing people.

As a litigator, I got to see sides of people that even their closest family didn't get to see. I got to know their darkest secrets and see them at their worst. I had to see all sides of a case. And that meant understanding and appreciating the complexities of human behavior. How there is no pure good and no pure evil. Everyone has a mix of both. And all actions really do create those pairs of opposites that have some sort of justification.

Any tips for breaking into filmmaking from a completely different profession?

Joseph Campbell talks about doors opening when you follow your bliss. I really believe that. I was a 31-year-old ACLU lawyer. I didn't know a single filmmaker and barely knew how to work a camera. But somehow I mustered up the courage to apply to NYU and was accepted with a full-tuition scholarship.

At NYU, I ended up making a film with James Franco and directed Olivia Wilde and Oscar-winner Whoopi Goldberg. Then I got a job working as a TA for Spike Lee, who gave me a grant to make my first feature-length doc. I really believe that fortune favors the bold. It's terrifying to leave a safe career for the unknown. But I feel like if you take that leap, you'll be helped by hidden hands.

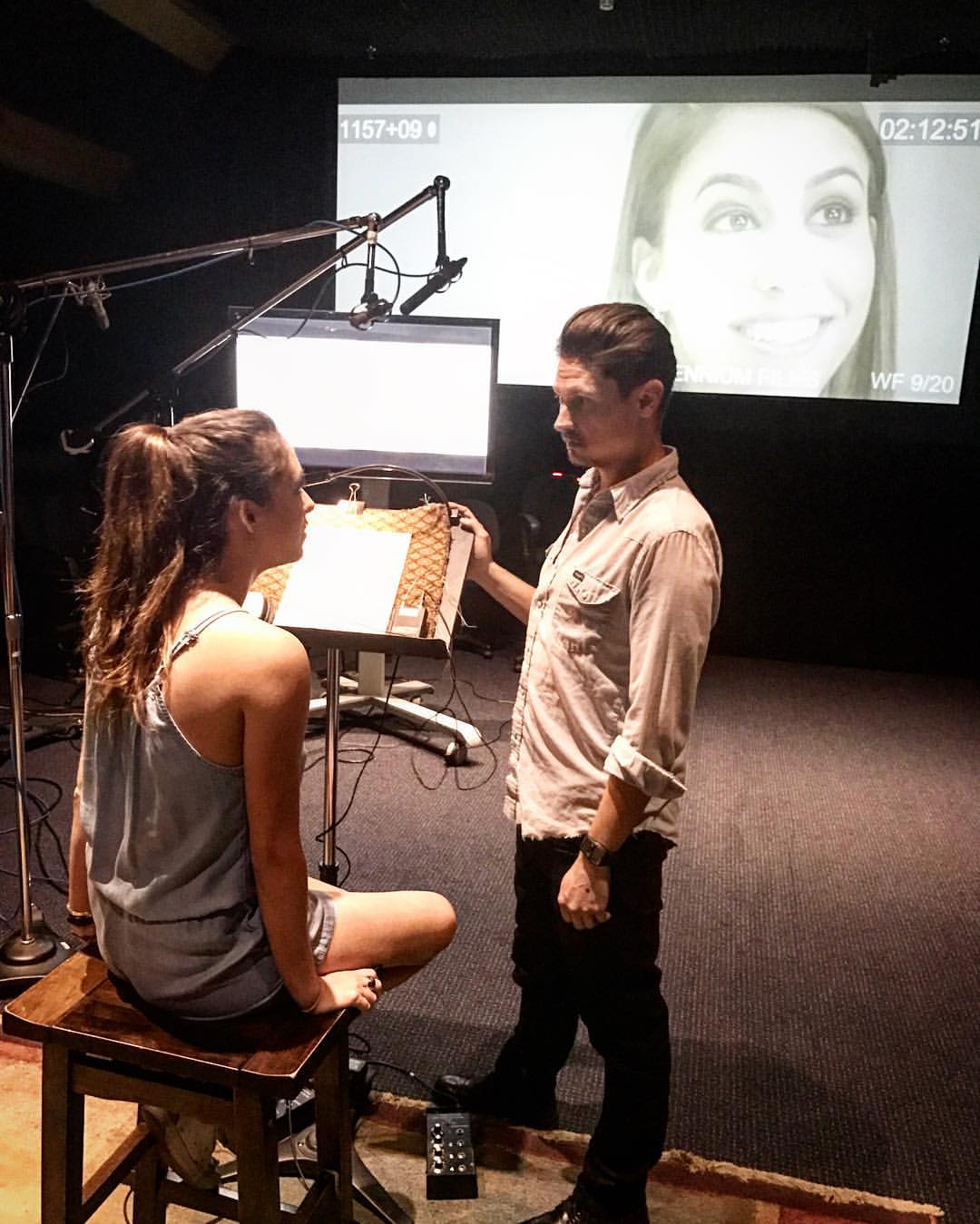

At Wildfire/Sonic Magic, directing ADR (additional dialogue recording) with actress Gabby Kono for feature film, Khali the Killer (Nu Image/Millennium)

At Wildfire/Sonic Magic, directing ADR (additional dialogue recording) with actress Gabby Kono for feature film, Khali the Killer (Nu Image/Millennium)[Photo Courtesy: Xander Lott]

Do you prefer fiction or non-fiction filmmaking (& why)?

I like both. When I'm working on a doc, non-fiction is my favorite. And when I'm working on a feature, fiction is my favorite. I like the variety. Not just in subject matter, but also in production. Sometimes it's nice to escape a big set and make a movie with just a camera and a microphone.

Also, with documentaries, I love being able to feed the social activist side of myself. I practiced public interest law for seven years. And I miss having a direct social impact. With docs, I feel like I can make an impact in ways that are even broader than law. Especially with the opioid problem. With this drug epidemic, the law isn't much of a solution. It's like putting a band-aid on a bleeding artery. But film can get to the source of the problem. It can figure out causes and solutions. It can help prevent problems before they start.

As an adjunct professor at Columbia College Hollywood, what is the most common mistake you see first time filmmakers making over and over again?

For me, I wasn't confident enough to understand criticism. I mean, it's still not easy. But I feel like I'm a little better at it, than when I first started making art. At that point, criticism would make me scrap a project. I thought something was either good or bad. Like their wasn't an in between. I didn't understand how to use notes to my advantage. If my work got criticized, I would just drop that project and start something else.

My students are actually way more confident than I was. But I think understanding criticism is hard for any artist. In my classes, the best work often gets the most notes. Good work provokes thought and stirs emotion. This translates into your peers being vocal about your work. This isn't a bad thing. It's actually an amazing thing. I wish I could go back in time and explain that to my younger self.

I understand you received a grant from Spike Lee for your first documentary "Surviving Cliffside". If you're willing to share, what was the amount for that film grant and how much total did you raise for that film? Any fundraising tips? Where have you found the most success in the area of documentary film funding?

I'm not sure I can talk about specific budget and grant stuff. But it was super low. I mean, Cliffside's entire budget was less than $50,000. And even after selling the film to the Sundance Channel, we barely put a dent in what we spent.

As far as fundraising goes, I come from the non-profit world. As an ACLU board member, we had to solicit member donations ourselves. Each board member learned how to do this. And we had to break out of our comfort zones and do it. This really translated into doc fundraising. I mean, if you're passionate about an important cause, it's easier to ask for funds for it. I've also hired fundraisers from the non-profit world to raise money for my docs. A lot of those skills really do transfer. It's all about believing in a a cause (your film), and having the courage enough to ask for the money to fund it.

Is there one area of the documentary making process where you feel you've had a huge learning curve? If so, share what that was and the lessons you learned?

In the commentary to Who's That Knocking at My Door, Scorsese talks about how he chooses shots. And how that's directly relates to how he physically sees the world. He talks fast. He observes everything. He's always bobbing and swiveling his head to see what's in the subway car behind him or the police car whizzing down the street. So this translates to whip pans, fast dollies, and zooms.

With me, I'm very near sighted. I wear like a -9 prescription. So I tend to get very close to subjects. Like too close. I've really had to back away from this. I'll get in the cutting room and have reels full of close ups. I've had to train myself to remember to get the wide shots. Get the establishing shots, even if you think you'll never use them. To not go too close, too fast. That kind of thing.

Now days, I've really fallen in love with the wide shot. Maybe even to the extreme. I love Bruno Dumont's incredibly epic wide shots and the blocking he uses inside those static frames.

Actually, my eye sight has improved in my late thirties. Maybe that has something to do with it.

Jon Matthews being interviewed by BBC Radio about Opioid Inc documentary

Jon Matthews being interviewed by BBC Radio about Opioid Inc documentary[Photo Courtesy: Tijah Bumgarner]

Any tips on how to use a documentary to make social impact/change? Is that what you're doing with Opioid Inc?

In Opioid Inc., I had some pretty incredible statistics to work with. 30 percent of all babies born in WV are born addicted. In some counties, that's as high as 50 percent. These are very powerful statistics. But I'm not doing a news article or a power point presentation. I had to find a way to make these numbers pay off cinematically. So, I went to a NICU. I filmed babies who were suffering from withdrawal. I went to a health clinic that treats babies who are born addicted. I showed the facilities waiting room that was filled with pop-up baby books next to the big book of Narcotics Anonymous.

I think when you're doing a film that has such incredible numbers, you can get lazy. But you have create a visual way to tell the story of the numbers in a way that creates the hardest emotional punch.

Any final advice for first time doc filmmakers?

Well, I had the opportunity to meet Al Maysels and I asked him this very question. He said, "Get close." I may have taken that too literally with all my close ups. But I think what he meant was to get close to your subjects. I'm not the smartest filmmaker. I don't always come up with the coolest shots. I don't always blow your mind with creative camera movement. But I'm easy to get along with. I think this is my most valuable skill. People feel comfortable around me. So they're more apt to open up.

I try to spend time with a subject before I start shooting. I have a meal with them, get coffee with them, or go for a walk. I get to know them, as much as I can, before I point all this weird camera and audio equipment at them. The more time I can spend with them off camera, the more it pays off on camera.

About Jon Matthews

Jon is a former ACLU lawyer turned filmmaker. He grew up in a hollow, called Booger Hole, in Alum Creek, West Virginia. Jon practiced civil rights law for seven years, including working as legal director for the ACLU of Connecticut.

At 31, Jon decided to give up law and enroll in NYU's graduate film program. At NYU, Jon studied under James Franco, Todd Solondz, Ira Sachs, and Spike Lee. Jon also worked as Spike Lee's teaching assistant, during his third year at NYU. In the spring of 2012, Jon co-directed a film with James Franco and ten NYU classmates. The film was produced by James Franco and stars Whoopi Goldberg, James Franco, Olivia Wilde, and Logan Marshall-Green. In January 2013, Jon received a grant, awarded by Spike Lee, to finish his documentary, Surviving Cliffside, his first feature documentary.

Jon is currently in post production on a film that he wrote and directed, called Khali the Killer. The film stars Emmy nominee, Richard Cabral, and is set to be released Summer 2017. His documentary Opioid, Inc is also scheduled for broadcast this summer on West Virginia Public Broadcasting. In addition, he is a co-producer for the documentary HILLBILLY (Co-Directed by Ashley York and Sally Rubin) currently in production.

Ready To Make Your Dream Documentary?

Sign up for our exclusive 7-day crash course and learn step-by-step how to make a documentary from idea to completed movie!

New! Comments

[To ensure your comment gets posted, please avoid using external links/URL's]