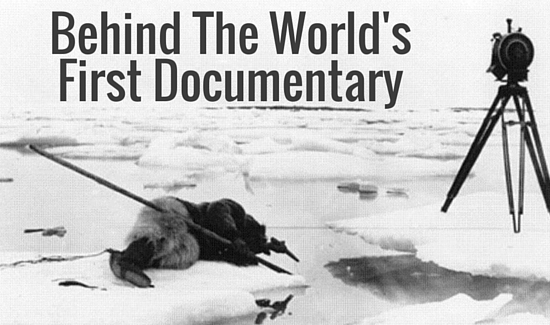

Behind The World's

First Documentary

(And What Today's Filmmakers Can Learn From It)

Guest Article By: Daniel Cantagallo

Many have proclaimed it is the golden age of documentaries and, with Sundance 2016 just wrapped up, there has been a lot of rich and vibrant conversation around the form (what it is and what it isn't).

I thought it would be illuminating to write

not only about the first “documentary”, but the spirit and

conditions under which it was made as inspiration for filmmakers embarking on their own films, just as Robert Flaherty did over 100 years ago.

"Nanook of the North" (1922) - Robert Flaherty

Behind The World's First Documentary

IN THE BEGINNING, there was ice and there was fire.

Beyond where the trees end, into the shivery mysteries of the icy North, handcranking away like a wild man on a mission, documenting the Igloobuilding, conjuring, dances, and sledging of the indigenous inhabitants, Robert Flaherty exposed over 70,000 feet of film stock.

Searching for iron ore on behalf of the burgeoning Canadian Northern transcontinental railway, Flaherty carried along a Bell and Howell 16mm motion picture camera he bought in New York.

The plan was to make visual notes of the area along on the way to the remote Baffin and Belcher Islands. While the mineral deposits he found were not up to grade for excavating, he did discover something else along the way: the filmmaking bug.

I was an explorer first and a filmmaker a long way after.

Flaherty spent much of his youth scurrying along the edges of civilization. He lived a nomadic lifestyle as a surveyor and geological prospector in the itinerant and dangerous world of mineral claims. Without any particular formal training*, he reminds us that above all documentary is an expedition into the unknown, whether it be uncharted lands or the treacherous territory of the human heart. One of the genre’s earliest practitioners, Flaherty was not an anthropologist or a scientist; he was an explorer.

*Robert Flaherty took a three-week camera work and processing course at Eastman Kodak in Rochester, NY when he bought the Bell & Howell camera. There is also an apochryal story Flaherty told about a missionary who showed him some of the basics. According to Flaherty, the missionary was later found dead, hanging in a hut that he had converted into a dark room.

When he finally came in from the Arctic cold several years later, Flaherty set up shop in a dark room in Toronto. Encouraged by his wife, Frances, his great collaborator and artist in her own right, he set about assembling his footage into fairly prosaic episodes. Painstakingly completed, Flaherty was packing up the material for his project when particles of ash floated down from his cigarette, igniting the negative. He desperately tried to put it out to no avail. Years of toil and hard work gone in a fiery blaze.**

**Documentary legend D.A. Pennebaker has speculated that Flaherty did not like the film and intentionally destroyed it himself.

Though it seemed to be a tragedy at the

time, I am not sure but it was a bit of fortune that it did burn, for it was amateurish enough.

Before the fire, Flaherty did have a positive print of the film struck (known as “The Harvard Print”), which he showed to friends and people at the American Geographic Society and the Explorer’s Club in New York. But its reception had thoroughly disappointed him. Viewers were more interested in where he had been and what he had done, rather than in the taking any particular interest in the guts and grace of the Inuit people themselves.

An explorer first, Flaherty was becoming an artist. Setting things right for his subject would become his obsession, and in a way, modern documentary filmmaking would be born from those remains of melted celluloid.

I wanted to show the Eskimo [Inuit].

And I wanted to show them, not from the civilized point of view, but as they saw themselves, as, “we the

people.” I realised then that I must go work in an entirely different way....I had learned to explore, I had

not learned to reveal. It was utterly inept, simply a scene of this

and that, no relation, no thread of a story

or continuity whatever... Certainly it bored me.”

What Flaherty realized was that he had made a fairly dull “travelogue,” a genre for academic types and tourists, good for the illustrated lecture circuit that existed at the time. He wanted to show...to reveal...not to tell an audience about the world of the Inuit.

Many travel films at the time were financed by railroad companies as advertising and publicity for the increasing commodification of the frontier. While he was very much part of that colonizing process dimming the purity of those landscapes and people Flaherty also loved them. It became his passion and life’s work to document the Inuits’ way of life before it vanished from their memories completely.*** Filmmaking as both an index of time passing, a preserving act and a revelation of the present moment of rapturous beauty.

...by taking a central character and portraying his exciting adventures, and those in his family, in the effort to wrest a livelihood from the frigid Arctic, we secure a dramatic value which is both legitimate and absorbing.

***Flaherty is often accused of cheating and lying for filming scenes in Nanook of the North that were staged reenactments no longer practiced by Innuits as he depicted. Controversy over filmmaker intervention into the stream of reality and selection of its parts is the fulcrum of the genre throughout its history. Recent examples include Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing or Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos’ Making A Murderer.

The perfect alchemy of legitimate and absorbing is still the holy grail for filmmakers engaged in nonfiction. Faithful to the facts, but not enslaved by them. In search of a point of view that expresses a deeper truth about human experience.

Flaherty would go on to complete Nanook of the North, considered to be the first documentary of the genre, eight years after his experiment with moviemaking began.

In order to create resonance, drama, and story, Flaherty cleverly absorbed the tools and techniques of narrative fiction: casting, direction, performance, reenactment, selection and montage. This liminal space between fiction and real life is where the genre always seems to replenish its innovation and creativity, while remaining hotly contested and fought over by ideologues.

One thing is clear in the heady haze...beyond where the trees end....that’s where you will find documentary.

About The Author

Daniel Cantagallo specializes in cutting-edge non-fiction content. A graduate of Harvard University’s Visual and Environmental Studies program, he also obtained his Master’s in Film Production from the London Film School. He coproduced and cowrote Shadows of Liberty, an investigation into the corporate control of US media, which received a Most Valuable Documentary nomination at the Cinema For Peace Awards and Best Documentary at NewFilmmakers Los Angeles. He currently works for Cargo Film & Releasing, a boutique documentary sales agency based in New York.

Please leave a comment below to let Daniel know your thoughts about his article.

Other Articles You May Enjoy

- Making Documentaries: What Camera Should I Buy?

- Documentary Fundraising: How To Find Money For Your Film

- How To Choose Your Next Documentary Idea

Ready To Make Your Dream Documentary?

Sign up for our exclusive 7-day crash course and learn step-by-step how to make a documentary from idea to completed movie!

New! Comments

[To ensure your comment gets posted, please avoid using external links/URL's]